…and all the best for 2011 to our clients, partners and readers!

PS: Based on a special request from a reader, it is now Anton who is sending our wishes.

Solving the terminology puzzle, one posting at a time

Each time a new project is kicked off this question is on the table. Content publishers ask how much are we expected to document. Localizers ask how many new terms will be used.

Who knows these things when each project is different, deadlines and scopes change, everyone understands “new term” to mean something else, etc. And yet, there is only the need to agree on a ballpark volume and schedule. With a bit of experience and a look at some key criteria, expectations can be set for the project team.

In a Canadian study, shared by Kara Warburton at TKE in Dublin, authors found that texts contain 2-4% terms. If you take a project of 500,000 words, that would be roughly 15,000 terms. In contrast, product glossary prepared for end-customers in print or online contain 20 to 100 terms. So, the discrepancy of what could be defined and what is generally defined for end-customers is large.

A product glossary is a great start. Sometimes, even that is not available. And, yet, I hear from at least one customer that he goes to the glossary first and then navigates the documentation. Ok, that customer is my father. But juxtapose that to the remark by a translator at a panel discussion at the ATA about a recent translation project (“aha, the quality of writing tells me that this falls in the category of ‘nobody will read it anyway’”), and I am glad that someone is getting value out of documentation.

In my experience, content publishing teams are staffed and ready to define about 20% of what localizers need. Ideally, 80% of new terms are documented systematically in the centralized terminology database upfront and the other 20% of terms submitted later, on an as-needed basis. Incidentally, I define “new terms” as terms that have not been documented in the terminology database. Anything that is part of a source text of a previous version or that is part of translation memories cannot be considered managed terminology.

In my experience, content publishing teams are staffed and ready to define about 20% of what localizers need. Ideally, 80% of new terms are documented systematically in the centralized terminology database upfront and the other 20% of terms submitted later, on an as-needed basis. Incidentally, I define “new terms” as terms that have not been documented in the terminology database. Anything that is part of a source text of a previous version or that is part of translation memories cannot be considered managed terminology.

Here are a few key criteria that help determine the number of terms to document in a terminology database:

These criteria can serve as guidelines, so that a project teams knows whether they are aiming at documenting 50 or 500 terms upfront. If memory serves me right, we added about 2700 terms to the database for Windows Vista. 75% was documented upfront. It might be worthwhile to keep track of historic data. That enables planning for the next project. Of course, upfront documentation of terms takes planning. But answering questions later is much more time-consuming, expensive and resource-intense. Hats off to companies, such as SAP, where the localization department has the power to stop a project when not enough terms were defined upfront!

Well, actually we do. They are an important part of the English language. But more often than not do they get used incorrectly in writing and, what’s worse, documented incorrectly in terminology entries.

I have been asked at least a few times by content publishers whether they can use gerunds or whether a gerund would present a problem for translators. It doesn’t present a problem for translators, since translators do not work word for word or term for term (see this earlier posting). They must understand the meaning of the semantic unit in the source text and then render the same meaning in the target language, no matter the part of speech they choose.

It is a different issue with machine translation. There is quite a bit of research in this area of natural language processing. Gerunds, for example, don’t exist in the German language (see Interaction between syntax and semantics: The case of gerund translation). But more importantly, gerunds can express multiple meanings and function as verbs or nouns (see this article by Rafael Guzmán). Therefore, human translators have to make choices. They are capable of that. Machines are not. If you are writing for machine translation and your style guide tells you to avoid gerunds, you should comply.

Because gerunds express multiple meanings, they are also interesting for those of us with a terminologist function. I believe they are the single biggest source of mistakes I have seen in my 14 years as corporate terminologist. Here are a few examples.

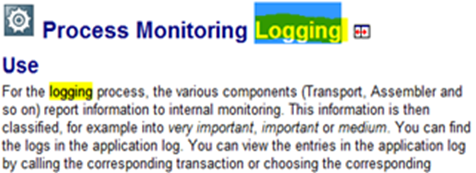

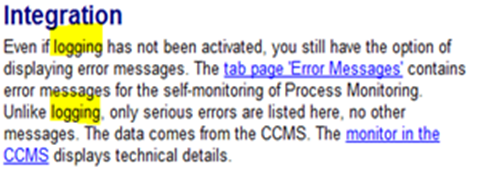

| Example 1: | Example 2: |

|

|

In Example 1, it is clear that logging refers to a process. The first instance could be part of the name of a functionality, which, as the first instance in Example 2 shows, can be activated. In the second instance (“unlike logging”) is not quite clear what is meant. I have seen logging used as a synonym to the noun log, i.e. the result of logging. But here, it probably refers to the process or the functionality.

It matters what the term refers to; it matters to the consumer of the text, the translator, who is really the most critical reader, and it matters when the concepts are entered in the terminology database. It would probably be clearest if the following terms were documented:

Another example of an –ing form that has caused confusion in the past is the term backflushing. A colleague insisted that it be documented as a verb. To backflush, the backflushing method or a backflush are curious terms, no doubt (for an explanation see Inventoryos.com). But we still must list them in canonical form and with the appropriate definition. Why? Well, for one thing, anything less than precise causes more harm than good even in a monolingual environment. But what is a translator or target terminologist to do with an entry where the term indicates that it is an adjective, the definition, starts with “A method that…”, and the Part of Speech says Verb? Hopefully, they complain, but if they don’t and simply make a decision, it’ll lead to errors. Human translators might just be confused, but the MT engine won’t recognize the mistake.

So, the answer to the question: “Can I use gerunds?” is, yes, you can. But be sure you know exactly what the gerund stands for. The process or the result? If it is used as a verb, document it in its canonical form. Otherwise, there is trouble.