Giving a new concept a name in a source language often leads directly to the question of what to do with it in another language. This seems like a problem for target terminologists and translators, right? It isn’t. Marketing, branding and content publishing folks listen up!

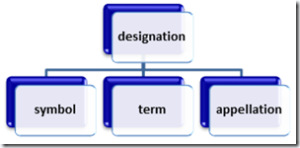

We have just created a new term or appellation according to best practices from ISO 704. Now, what do we call it in the target language? What do we do with new designations, such as Azure or jump list? Well, the same best practices apply for target language terms as well. But there is a difference for terms and appellations.

Terms represent generic concepts. They are the parent concept or superordinate to other concepts. The concept called “operating system” in English has many different subordinate concepts, e.g. Windows, Linux, or Mac OS. Many times generic concepts have native-language equivalents in other languages. Of course, a particular language may borrow a term from another language, a direct loan. But that should be a deliberate term formation method and it is just one of them, as discussed in What I like about ISO 704.

Terms represent generic concepts. They are the parent concept or superordinate to other concepts. The concept called “operating system” in English has many different subordinate concepts, e.g. Windows, Linux, or Mac OS. Many times generic concepts have native-language equivalents in other languages. Of course, a particular language may borrow a term from another language, a direct loan. But that should be a deliberate term formation method and it is just one of them, as discussed in What I like about ISO 704.

An appellation represents an individual concept, one that is unique. Like you and me. And just as our parents gave us names that should represent us to the world—some very common and transparent, others peculiar or extraordinary—products get names that represent them to buyers. The criteria for good formation are weighted slightly differently than they are when used during new term formation: An appellation might be deliberately not transparent or consistent with the rest of the subject field. After all, it is a new product that is supposed to stand out. And it might be deliberately in another language.

Windows Azure™ is the appellation for “a cloud services operating system that serves as the development, service hosting and service management environment for the Windows Azure platform,” according to the official website. If we leave aside the trademark for a moment, nobody in their right mind would use the literal translations “Fenster ‘Azurblau’”, “Fenêtre bleu” or “Finestra azzurra”.

Once again, I find ISO 704 very helpful: “Technically, appellations are not translated but remain in their original language. However, an individual concept may have an appellation in different languages.” Good examples are international organizations which tend to have appellations in all languages of the member states, such as the European Union, die Europäische Union, or l’Union européenne.

Once again, I find ISO 704 very helpful: “Technically, appellations are not translated but remain in their original language. However, an individual concept may have an appellation in different languages.” Good examples are international organizations which tend to have appellations in all languages of the member states, such as the European Union, die Europäische Union, or l’Union européenne.

ISO 704 goes on to say that “whether an individual concept has an appellation in more than one language depends on the following:

- The language policy of a country;

- How internationally well known the concept is;

- The multilingual nature of the entity in question;

- The need for international cooperation and relations.”

Based on this, it is pretty clear that an international organization would have an appellation in each of the languages of the member states. What about product names, such as Windows Azure? As terminologists for the target market, we should make recommendations in line with the above.

That is exactly what happened with a new feature for Windows 7, called Jump List in English. The message from the marketing department was that it was to remain in English even in the localized versions of Windows. But the problem wasn’t that simple.

There are actually two concepts hidden behind this name:

There are actually two concepts hidden behind this name:

- Jump List: The Windows feature that allows users to display jump lists.

- A unique feature and therefore an individual concept.

- An appellation.

- jump list: A list associated with programs pinned to the taskbar or Start menu.

- A generic concept that can happen multiple times even within one session

- A technical term.

- Erroneously capitalized in English.

Generally, when a new feature is introduced the feature gets a name and many times, the individual instances of the feature take on a term derived from the feature name. In this case, the feature was named Jump List and the instances were called Jump Lists. The later should not be uppercase and is in many instances not uppercase. But the two concepts were not differentiated, let alone defined up front.

So, when the German localizers got the instruction to keep the English term for all instances of the concept, they had a problem. They would have gotten away with leaving the appellation in English (e.g. Jump List-Funktion), but it would have been nearly impossible to get the meaning of the generic concept across or even just read the German text, had the term for the generic concept been the direct loan from the English. We could argue whether the literal translation Sprungliste represents the concept well to German users.

Naming is tricky, and those who name things must be very clear on what it is they are naming. Spelling is part of naming, and casing is part of spelling. Defining something upfront and then using it consistently supports clear communication and prevents errors in source and target texts.

Imagine you have a large document to author or translate. Your client gave you a dictionary to use. Because you are not sure of the meaning or usage of 50 terms, you look them up. But the dictionary holds you up more than anything: One entry contains a definition, the next one doesn’t; one provides context, but it is in a language you don’t understand; most terms make sense, but several of them are cryptic and the entry doesn’t provide clarity. If your client hadn’t insisted that you use the dictionary, you wouldn’t: It just slows you down.

Imagine you have a large document to author or translate. Your client gave you a dictionary to use. Because you are not sure of the meaning or usage of 50 terms, you look them up. But the dictionary holds you up more than anything: One entry contains a definition, the next one doesn’t; one provides context, but it is in a language you don’t understand; most terms make sense, but several of them are cryptic and the entry doesn’t provide clarity. If your client hadn’t insisted that you use the dictionary, you wouldn’t: It just slows you down. The Microsoft terminology team did. Simply handing a standards document off to the team had not been successful in the past—nobody could remember it, many entries therefore contained unstructured, if not incorrect information, and there was no incentive to adhere to standards. A more collaborative effort was called for: Together, in-house terminologists went through data categories one by one. Because we were a virtual team, e-mail was the best form of communication. Each data category was dealt with in one e-mail that contained: the definition, a scenario and voting buttons that allowed the team to agree with the meaning or disagree and make a better suggestion. Team members could participate in the voting, but they didn’t have to. However, anyone knew from the beginning that they had to accept the outcome, regardless of whether they participated or not. After the new guide had been published, measurements were carried out and documented in a quarterly report. Terminologists then set their own deadlines for cleaning up entries to comply with the standards.

The Microsoft terminology team did. Simply handing a standards document off to the team had not been successful in the past—nobody could remember it, many entries therefore contained unstructured, if not incorrect information, and there was no incentive to adhere to standards. A more collaborative effort was called for: Together, in-house terminologists went through data categories one by one. Because we were a virtual team, e-mail was the best form of communication. Each data category was dealt with in one e-mail that contained: the definition, a scenario and voting buttons that allowed the team to agree with the meaning or disagree and make a better suggestion. Team members could participate in the voting, but they didn’t have to. However, anyone knew from the beginning that they had to accept the outcome, regardless of whether they participated or not. After the new guide had been published, measurements were carried out and documented in a quarterly report. Terminologists then set their own deadlines for cleaning up entries to comply with the standards.