Let’s continue in our series of designators (remember, these are terms, appellations and symbols) to include in a terminology database. Today, we will focus on the question: Can this designator be confused with another? More specifically, is there a homograph that stands for a different concept?

Homographs—words that have the same spelling, but differ from one another in meaning, origin, and sometimes pronunciation—are probably the most frequent source of confusion. While we try not to use one term for multiple things, it cannot always be avoided; language is alive, meaning evolves, and even with the best prescriptive terminology management system, you might encounter homographs.

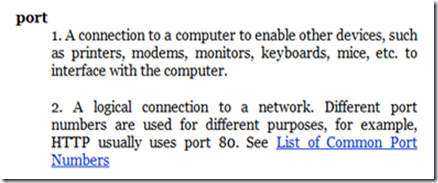

A good example is the term port. Port has many meanings as a word in general language and as a term in special languages. In the IT world, it can refer to at least a physical piece of hardware and a logical piece of software.

A good example is the term port. Port has many meanings as a word in general language and as a term in special languages. In the IT world, it can refer to at least a physical piece of hardware and a logical piece of software.

Theoretically, when there is the risk of “confusability,” the technical writer should be very specific, for instance, by using physical port or hardware port or even more specifically keyboard port. But even if the writer is precise in the first occurrence of the concept in the text, s/he may use the more generic or abbreviated form port in subsequent parts of the text or on the user interface. Because we never know what shows up in the translation environment first, though, it is good to alert a localizer to the fact that there are multiple meanings behind the term and include it in the terminology database.

So, if the answer to the question “is there a risk of confusability?” is yes, add the term and its homograph to the terminology database. While users of the database still need to identify the meaning in their context, at least they are alerted to the fact that there are two or more possible meanings.

Tomorrow, we will discuss selecting terms based on their degree of specialization.

Let’s start with terms that have gone through what is called “terminologization”—the process by which a general-language word or expression is transformed into a term designating a concept in a

Let’s start with terms that have gone through what is called “terminologization”—the process by which a general-language word or expression is transformed into a term designating a concept in a  Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is.

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is. For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead:

For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead: