Well, actually we do. They are an important part of the English language. But more often than not do they get used incorrectly in writing and, what’s worse, documented incorrectly in terminology entries.

I have been asked at least a few times by content publishers whether they can use gerunds or whether a gerund would present a problem for translators. It doesn’t present a problem for translators, since translators do not work word for word or term for term (see this earlier posting). They must understand the meaning of the semantic unit in the source text and then render the same meaning in the target language, no matter the part of speech they choose.

It is a different issue with machine translation. There is quite a bit of research in this area of natural language processing. Gerunds, for example, don’t exist in the German language (see Interaction between syntax and semantics: The case of gerund translation). But more importantly, gerunds can express multiple meanings and function as verbs or nouns (see this article by Rafael Guzmán). Therefore, human translators have to make choices. They are capable of that. Machines are not. If you are writing for machine translation and your style guide tells you to avoid gerunds, you should comply.

Because gerunds express multiple meanings, they are also interesting for those of us with a terminologist function. I believe they are the single biggest source of mistakes I have seen in my 14 years as corporate terminologist. Here are a few examples.

| Example 1: | Example 2: |

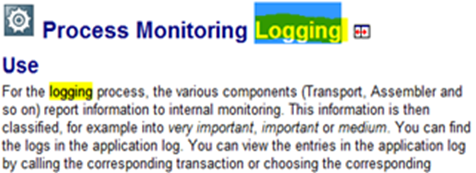

|

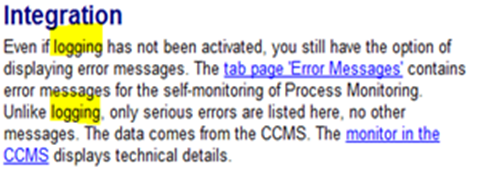

|

In Example 1, it is clear that logging refers to a process. The first instance could be part of the name of a functionality, which, as the first instance in Example 2 shows, can be activated. In the second instance (“unlike logging”) is not quite clear what is meant. I have seen logging used as a synonym to the noun log, i.e. the result of logging. But here, it probably refers to the process or the functionality.

It matters what the term refers to; it matters to the consumer of the text, the translator, who is really the most critical reader, and it matters when the concepts are entered in the terminology database. It would probably be clearest if the following terms were documented:

- logging = The process of recording actions that take place on a computer, network, or system. (Microsoft Language Portal)

- logging; log = A record of transactions or events that take place within an IT managed environment. (Microsoft Language Portal)

- Process Monitoring logging = The functionality that allows users to …(BIK based on context)

- log = To record transactions or events that take place on a computer, network or system. (BIK based on Microsoft Language Portal).

Another example of an –ing form that has caused confusion in the past is the term backflushing. A colleague insisted that it be documented as a verb. To backflush, the backflushing method or a backflush are curious terms, no doubt (for an explanation see Inventoryos.com). But we still must list them in canonical form and with the appropriate definition. Why? Well, for one thing, anything less than precise causes more harm than good even in a monolingual environment. But what is a translator or target terminologist to do with an entry where the term indicates that it is an adjective, the definition, starts with “A method that…”, and the Part of Speech says Verb? Hopefully, they complain, but if they don’t and simply make a decision, it’ll lead to errors. Human translators might just be confused, but the MT engine won’t recognize the mistake.

So, the answer to the question: “Can I use gerunds?” is, yes, you can. But be sure you know exactly what the gerund stands for. The process or the result? If it is used as a verb, document it in its canonical form. Otherwise, there is trouble.

Throughout the history, any language has always incorporated foreign words and phrases, to paraphrase Darwin, this was the development and “origin of languages by natural selection”. These days, most new words are English, predominantly American English to be precise. All historical attempts to “purify” a particular language proved largely unsuccessful, and many people, including linguists, doubt seriously that such efforts would fare any better today. English has already invaded the languages of Molière, Cervantes and Goethe, dominating above all the fields of technology and business, and spreading widely with the young generations and their jargon. Denglisch, Franglais, Spanglish, Swenglist, Slogleščina and the like were born, a natural linguistic blend of two languages bringing together their morphological, syntactical and phonetic peculiarities in one sentence, often in a single word as well. It occurs mostly in sports, computing, and business where the domestic language, for some reason or the other, lacks words for some concepts, like the word “serve” in tennis, or the domestic word is less well known, e.g. “stock options”. It also occurs when a word is to be “modernized”, shortened or otherwise updated, like “outsourcing” in business, where people go to the “office”, attend “meetings”, work in “teams”, participate in “workshops” and consider “stock markets” in a number of languages. In Slovene, for example, the situation is even more complex because it is a highly inflected language (a single verb, noun, adjective has a vast number of different endings as a rule) and has an almost “phonetic” writing, so we may encounter doublets like tagirati / tegirati (to tag), tagiranje / tegiranje and the shorter version taganje / teganje (tagging) or verbs like surfati, torrentati (mind the double r, which is not a Slovene feature), printati, downloadati (w is not Slovene), keširanje (I am sure you can understand them, I should help you perhaps with the last one – caching).

Throughout the history, any language has always incorporated foreign words and phrases, to paraphrase Darwin, this was the development and “origin of languages by natural selection”. These days, most new words are English, predominantly American English to be precise. All historical attempts to “purify” a particular language proved largely unsuccessful, and many people, including linguists, doubt seriously that such efforts would fare any better today. English has already invaded the languages of Molière, Cervantes and Goethe, dominating above all the fields of technology and business, and spreading widely with the young generations and their jargon. Denglisch, Franglais, Spanglish, Swenglist, Slogleščina and the like were born, a natural linguistic blend of two languages bringing together their morphological, syntactical and phonetic peculiarities in one sentence, often in a single word as well. It occurs mostly in sports, computing, and business where the domestic language, for some reason or the other, lacks words for some concepts, like the word “serve” in tennis, or the domestic word is less well known, e.g. “stock options”. It also occurs when a word is to be “modernized”, shortened or otherwise updated, like “outsourcing” in business, where people go to the “office”, attend “meetings”, work in “teams”, participate in “workshops” and consider “stock markets” in a number of languages. In Slovene, for example, the situation is even more complex because it is a highly inflected language (a single verb, noun, adjective has a vast number of different endings as a rule) and has an almost “phonetic” writing, so we may encounter doublets like tagirati / tegirati (to tag), tagiranje / tegiranje and the shorter version taganje / teganje (tagging) or verbs like surfati, torrentati (mind the double r, which is not a Slovene feature), printati, downloadati (w is not Slovene), keširanje (I am sure you can understand them, I should help you perhaps with the last one – caching).