I will soon get back to my regular schedule. In the meantime, here is another little article that I wrote for Ivan Kanič—a librarian and blogger, who writes about terminology issues for librarians in his native Slovenia. It’s been a pleasure working with Ivan on this little project. Check it out!

ROI—The J.D. Edwards Data from 2001

Even after nine years, the terminology ROI data from J.D. Edwards is still being quoted in the industry. The data made a splash, because it was the only data available at the time. It isn’t always quoted accurately, though, and since it just came up at TKE in Dublin, let’s revisit what the J.D. Edwards team did back then.

J.D. Edwards VP of content publishing, Ben Martin, was invited to present at the TAMA conference in Antwerp in February 2001. His main focus was on single-source publishing. Ben invited yours truly to talk more about the details of the terminology management system as part of his presentation, and he also encouraged a little study that a small project team conducted.

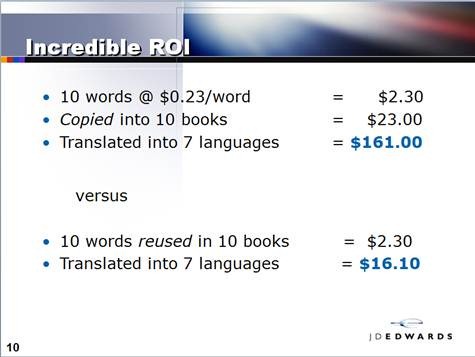

Ben’s argument for single-sourcing was and is simple: Write it once, reuse it multiple times; translate it once, reuse the translated chunk multiple times.

Ben’s argument for single-sourcing was and is simple: Write it once, reuse it multiple times; translate it once, reuse the translated chunk multiple times.

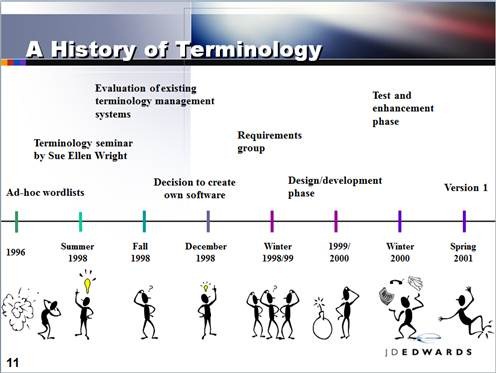

At that time, the J.D. Edwards’ terminology team and project was in its infancy. In fact, the TMS was just about to go live, as the timeline presented in Antwerp shows.

At that time, the J.D. Edwards’ terminology team and project was in its infancy. In fact, the TMS was just about to go live, as the timeline presented in Antwerp shows.

For the ROI (return on investment) study, my colleagues compared the following data:

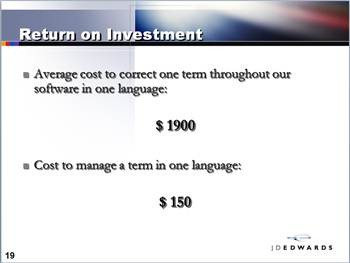

- What does it cost to change one term throughout the J.D. Edwards software and documentation?

- What does it cost to manage one concept/term?

27 different terms were changed in various languages, and the time it took was measured. Then, the average change time was multiplied by the average hourly translation cost, including overhead. In the J.D. Edwards setting, the average cost to change one term in one language turned out to be $1900.

The average time that it took to create one entry in the terminology database had already been measured. At that early time in the project, it cost $150 per terminological entry.

The average time that it took to create one entry in the terminology database had already been measured. At that early time in the project, it cost $150 per terminological entry.

The cost to manage one entry seems high. Therefore, it is important to note that

- There were three quality assurance steps in the flow of one entry for the source language English, and up to two steps in the flow of one entry for the target languages. So, the resulting entry was highly reliable, and change management was minimal.

- The cost came down dramatically over the months, as terminologists and other terminology stakeholders became more proficient in the process, standards and tool.

Both figures are highly system/environment-dependent. In other words, if it is easy to find and replace a term in the documents, it will cost less. While these figures were first published years ago, they served as the benchmark in the industry and established an ROI model that has since been used and further developed and elaborated on. If you have any opinion, thoughts or can share other information, feel free to add a comment or send me an e-mail.

What I like about ISO 704

The body of ISO 704 “Terminology work—Principles and methods” lists a bunch of important information for terminology work. But what stuck in my mind is actually the annexes, most of all Annex B.

In the current version 704:2009, Annex B is devoted to term-formation methods. In other words, it gives us the most important methods that we have available when creating new terms or appellations in English. It also notes what might be obvious to us, i.e. that these methods differ from language to language. For German, for example, we now have the new Terminologiearbeit – Best Practices which the German terminology association, DTT, published recently and which is more systematic about this topic than a standard might be.

Comprehensiveness need not be the goal of 704; awareness of these methods is more important. If half the content publishers, PMs, branding or marketing folks that I worked with in the IT world had read those five short pages, it would have done a world of good. Instead, I have heard colleagues mocking terminologists who, when coining new terms, pull out the Duden (the main German-German dictionary, similar to The Webster’s or Le Petit Robert) to apply one of these methods. She who laughs last, laughs best, though: New terms and appellations that are well-motivated—either rooted in existing language or deliberately different—last. Quickly invented garbage causes misunderstandings and costs money.

Annex B doesn’t claim to be comprehensive, but it lists the most important methods that can be used in term formation. Here are the three main methods and some examples:

- The first one is the creation of completely new lexical entities (terms or appellations), also known as neoterms. One way of creating a neoterm is through compounding, where a new designation is formed of two or more elements, for example cloud computing.

- Two methods that fall into the category of using existing forms are terminologization (see also How do I identify a term—terminologization) and transdisciplinary borrowing. An example of terminologization is cloud, where the everyday word cloud took on a very specific meaning in the context of computing, while the name of the computer virus Trojan horse was obviously borrowed from Greek mythology.

- Translingual borrowing results in new terms and appellations that originate in another language. English climbing language, for example, is full of direct loans from a variety of other languages; just think of bergschrund, cairn or scree.

The above are just a few examples to give you an impression of what could be learned by reading Annex B. Incidentally, these are methods. They need to be applied correctly, not randomly. I can already hear it, “but I used transdisciplinary borrowing to come up with this [junk]”. No. Even if your orthopedist uses minimally-invasive arthroscopic surgery to fix your knee, you want him to be sure that you actually need surgery, right? If you need to coin English terms or appellations on a regular basis, Annex B of ISO 704 is worth your while. I also like Annex C. More about that some other time.