In What is a term? our focus was on how to define the scope of a terminology database and guide a team on what should and what shouldn’t be entered into a terminology database. It is good to have rough guidelines, but there is obviously more to the story of what a term is and what should be included in a terminology database.

If we are asked to go through a list of term candidates extracted by a term extraction tool or if we are selecting terms manually, we may not always be sure whether a certain term candidate should be included. Especially if you are not a subject matter expert or if you only speak one language, this is a difficult job. It is a little easier for translators, as they are used to analyzing texts very thoroughly. As an aside, this quality makes the translator a content publisher’s best friend, for translators find the mistakes, the inconsistencies or just the minor hitches of a text. And yet in the term selection process, we have to make decisions in split seconds. How do we make them? This and the next eight postings—one short post over the next eight days—will provide more in-depth guidance on why a term should be included in a terminology database.

Let’s start with terms that have gone through what is called “terminologization”—the process by which a general-language word or expression is transformed into a term designating a concept in a language for special purposes (LSP)(ISO 704). This Microsoft Language Portal Blog posting gives a variety of examples for animal names, e.g. mouse or worm, that became technical terms in the IT industry. We are often able to distinguish terms that have undergone terminologization when we distinguish them from other terms in the conceptual vicinity (see Juan Sager’s A Practical Course in Terminology), e.g. dedicated line vs. public line.

Let’s start with terms that have gone through what is called “terminologization”—the process by which a general-language word or expression is transformed into a term designating a concept in a language for special purposes (LSP)(ISO 704). This Microsoft Language Portal Blog posting gives a variety of examples for animal names, e.g. mouse or worm, that became technical terms in the IT industry. We are often able to distinguish terms that have undergone terminologization when we distinguish them from other terms in the conceptual vicinity (see Juan Sager’s A Practical Course in Terminology), e.g. dedicated line vs. public line.

So, if we ask ourselves: Is it a word that became a term and is now used with a very specific meaning in technical language, and the answer is yes, let’s include it in the terminology database. Then there is no confusion about what we mean with it, because it is clearly defined, and its usage can be standardized across languages.

More on term selection and the criterion “confusability” next time.

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

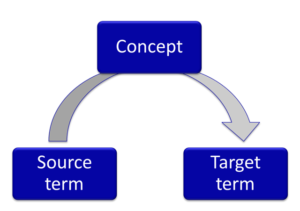

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is.

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is. For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead:

For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead: