And the final criterion in this blog series on how to identify terms is, in my mind, one of the most important ones—standardization. Standardized usage and spelling makes the life of the product user much easier, and it is fairly clear which key concepts need to be documented in a terminology database for that reason. But are they the same for target terms? And if not, how would we know what must be standardized for, say, Japanese? We don’t—that’s when we rely on process and tools.

Example 1. Before we got to standardizing terminology at J.D. Edwards (JDE), purchase orders could be pushed, committed or sent. And it all meant the same thing. That had several obvious consequences:

- Loss of productivity by customers: They had to research documentation to find out what would happen if they clicked Push on one form, Send on another or Commit on the third.

- Loss of productivity by translators: They walked across the hall, which fortunately was possible, to enquire about the difference.

- Inconsistency in target languages: If some translators did not think that these three terms could stand for the same thing (why would they?), they replicated the inconsistency in their language.

- Translation memory: Push purchase order, Commit purchase order and Send purchase order needed to be translated three times by 21 languages before the translation memory kicked in.

All this results in direct and indirect cost.

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying…

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying…

Example 3. Standardization to achieve consistency in the source language is self-evident. But what about the target side? Of course, we would want a team of ten localizers working on different parts of the same product to use the same terminology. One of the most difficult languages to standardize is Japanese. My former colleague and Japanese terminologist at JDE, Demi, explained it as follows:

For Japanese, “[…] we have three writing systems:

- Chinese characters […]

- Hiragana […]

- Katakana […].

We often mix Roman alphabet in our writing system too. […]how to mix the three characters, Chinese, Katakana, Hiragana, plus Roman alphabet, is up to each [person’s] discretion! For translation, it causes a problem of course. We need to come up with a certain agreements and rules.”

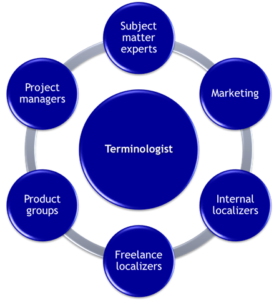

The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request.

The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request.

To sum up this series on how to identify terms for inclusion in a terminology database: We discussed nine criteria: terminologization, specialization, confusability, frequency, distribution, novelty, visibility, system and standardization. Each one of them weighs differently for each term candidate and most of the time several criteria apply. A terminologist, content publisher or translator has to weight these criteria and make a decision quickly. No two people will come up with the same list upfront. But tools and processes should support downstream requests.

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language

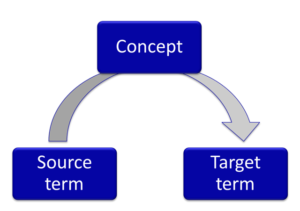

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is.

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is. For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead:

For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead: