One of the main reasons of having a concept-oriented terminology database is that we can set up one definition to represent the concept and can then attach all its designations, including all equivalents in the target language. It helps save cost, drive standardization and increase usability. Doublettes offset these benefits.

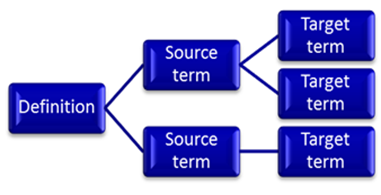

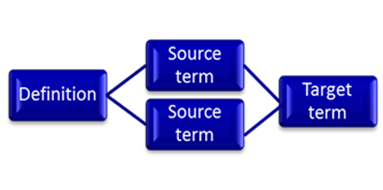

The below diagrams are simplifications, of course, but they explain visually why concept orientation is necessary when you are dealing with more than one language in a database. To explain it briefly: once the concept is established through a definition and other concept-related metadata, source and target designators can be researched and documented. Sometimes this research will result in multiple target equivalents when there was only one source designator; sometimes it is just the opposite, where, say, the source languages uses a long and a short form, but the target language only has a long form.

If you had doublettes in your database it not only means that the concept research happened twice and, to a certain level, unsuccessfully. But it also means that designators have to be researched twice and their respective metadata has to be documented twice. The more languages there are, the more expensive that becomes. Rather than having, say, a German terminologist research the concept denoted by automated teller machine, ATM and electronic cash machine, cash machine, etc. two or more times, research takes place once and the German equivalent Bankautomat is attached as equivalent potentially as equivalent for all English synonyms.

Doublettes also make it more difficult to work towards standardized terminology. When you set up a terminological entry including the metadata to guide the consumer of the terminological data in usage, standardization happens even if there are multiple synonyms. Because they are all in one record, the user has, e.g. usage, product, or version information to choose the applicable term for their context. But it is also harder to use, because the reader has to compare two entries to find the guidance.

And lastly, if that information is in two records, it might be harder to discover. Depending on the search functionality, the designator and the language of the designator, the doublettes might display in one search. But chances are that only one is found and taken for the only record on the concept. With increasing data volumes more doublettes will happen, but retrievability is a critical part of usability. And without usability, standardization is even less likely and even more money was wasted.

A few years ago, Maria Theresa Cabré rightly criticized Microsoft Terminology Studio when a colleague showed it at a conference, because the UI tab for target language entries said “Term Translations.” And if you talk to Klaus-Dirk Schmitz about translating terminology, you will for sure be set straight. I am absolutely with my respected colleagues.

A few years ago, Maria Theresa Cabré rightly criticized Microsoft Terminology Studio when a colleague showed it at a conference, because the UI tab for target language entries said “Term Translations.” And if you talk to Klaus-Dirk Schmitz about translating terminology, you will for sure be set straight. I am absolutely with my respected colleagues. At the end of the translation process, we have a translated text which in this form can only be used once. Of course, it might become part of a translation memory (TM) and be reused. But reuse can only happen, if the second product using the TM serves the same readership; if the purpose of the text is the same; if someone analyses the new source text with the correct TM, etc. And even then, it would be a good idea to proofread the outcome thoroughly.

At the end of the translation process, we have a translated text which in this form can only be used once. Of course, it might become part of a translation memory (TM) and be reused. But reuse can only happen, if the second product using the TM serves the same readership; if the purpose of the text is the same; if someone analyses the new source text with the correct TM, etc. And even then, it would be a good idea to proofread the outcome thoroughly.

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying…

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying… The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request.

The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request.