For the last several weeks, I have been working on terminology for the nicely regulated aviation industry where well-defined terminology is prevalent. It was perfect timing to learn about training, maintenance, and safety concepts in this industry, since in the midst of the assignment, I climbed into a floatplane (The Otter) and flew to Katmai National Park for four fascinating days.

For the last several weeks, I have been working on terminology for the nicely regulated aviation industry where well-defined terminology is prevalent. It was perfect timing to learn about training, maintenance, and safety concepts in this industry, since in the midst of the assignment, I climbed into a floatplane (The Otter) and flew to Katmai National Park for four fascinating days.

This park, located in the southwestern corner of Alaska, was founded following a volcanic eruption in 1912. The explosion of Novarupta was the largest volcanic event of the 20 century, and ashes could be found as far away as Africa. When researchers around Robert Griggs ventured back into the area, they found what they thought were small sources of fire still smoldering and dubbed the place ‘Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.’ Years later upon closer investigation, the “smoke” turned out to come from the Ukak River that had gotten buried underneath the lava. Instead of particles produced by combustion, water vapor was rising from the lava fields. The misnomer of the valley stuck, though, but outside of the proper noun, “smoke” has since been put in quotes on most boards and documents.

This park, located in the southwestern corner of Alaska, was founded following a volcanic eruption in 1912. The explosion of Novarupta was the largest volcanic event of the 20 century, and ashes could be found as far away as Africa. When researchers around Robert Griggs ventured back into the area, they found what they thought were small sources of fire still smoldering and dubbed the place ‘Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.’ Years later upon closer investigation, the “smoke” turned out to come from the Ukak River that had gotten buried underneath the lava. Instead of particles produced by combustion, water vapor was rising from the lava fields. The misnomer of the valley stuck, though, but outside of the proper noun, “smoke” has since been put in quotes on most boards and documents.

Inaccurate terminology in historic names is common. In fact, misleading terms could be considered an indication of progress in a subject field and incorrect names of landmarks even add to the places. I am glad, though, that terminology at the other attraction of the Park is being handled extremely carefully these days. I am referring to the Brooks River and its resident bear population.

From a safe platform, these large mammals can be observed catching fish in four distinct ways: Snorkeling which is the most effective and most popular technique; younger bears often engage in what is called the “dash-and-grab” technique of running in shallower water and snatching fish with the paw. If they are not successful and hunger really strikes, specialists switch to technique number three, stealing. The least popular, but most interesting to watch, is diving: After the bear head disappears in the green water of Naknek Lake, a pair of leathery feet emerges. Seconds later, the lucky diver pops back up with a red sockeye salmon in his jaw.

From a safe platform, these large mammals can be observed catching fish in four distinct ways: Snorkeling which is the most effective and most popular technique; younger bears often engage in what is called the “dash-and-grab” technique of running in shallower water and snatching fish with the paw. If they are not successful and hunger really strikes, specialists switch to technique number three, stealing. The least popular, but most interesting to watch, is diving: After the bear head disappears in the green water of Naknek Lake, a pair of leathery feet emerges. Seconds later, the lucky diver pops back up with a red sockeye salmon in his jaw.

Where bears and people live close together, rangers don’t have an easy task. People are to stay at least 50 yards from the bears, and even if you have the best intentions, you constantly need to be on your toes, in more than one sense of the word.

Where bears and people live close together, rangers don’t have an easy task. People are to stay at least 50 yards from the bears, and even if you have the best intentions, you constantly need to be on your toes, in more than one sense of the word.

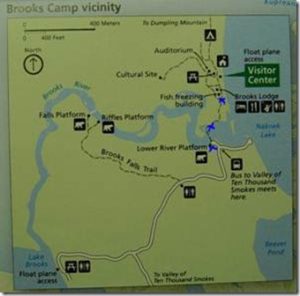

From 8 AM to 8 PM, rangers are stationed at three strategic places, roughly where you see the blue crosses on the adjacent map. It was highly interesting to listen to them inform each other about bear movement via two-way radio. One ranger was more precise and efficient in his or her communication than the next. And they all referred to places the same way: For example, the lowest cross is close to “the platform;” the next cross up was a place called “corner.” The corner and the platform were connected via a small floating bridge (“the bridge”). And to the East of the corner was a little promontory referred to as “the point.” Rangers described pathways of bears very clearly, so that each ranger always knew when to move people away from a spot or when the bridge could be approached, even though the terrain was covered by forest.

While names of most landmarks had emerged over the years, returning rangers drew up a map to define important places for newcomers. Naming was logical and communication was adjusted seamlessly to recipient (fellow ranger or guest) and method (radio or face-to-face). While this might seem an obvious behavior, it is one that clearly contributes to the safety of the environment. Besides these professional observations, my father and I had an incredible time at Katmai National Park.

While names of most landmarks had emerged over the years, returning rangers drew up a map to define important places for newcomers. Naming was logical and communication was adjusted seamlessly to recipient (fellow ranger or guest) and method (radio or face-to-face). While this might seem an obvious behavior, it is one that clearly contributes to the safety of the environment. Besides these professional observations, my father and I had an incredible time at Katmai National Park.