Even after nine years, the terminology ROI data from J.D. Edwards is still being quoted in the industry. The data made a splash, because it was the only data available at the time. It isn’t always quoted accurately, though, and since it just came up at TKE in Dublin, let’s revisit what the J.D. Edwards team did back then.

J.D. Edwards VP of content publishing, Ben Martin, was invited to present at the TAMA conference in Antwerp in February 2001. His main focus was on single-source publishing. Ben invited yours truly to talk more about the details of the terminology management system as part of his presentation, and he also encouraged a little study that a small project team conducted.

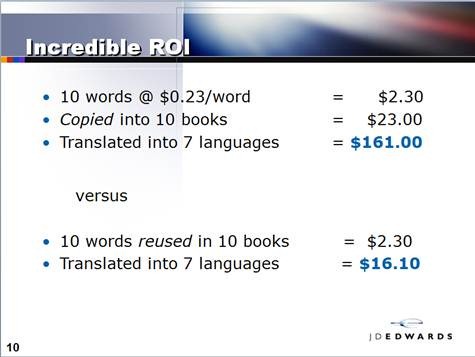

Ben’s argument for single-sourcing was and is simple: Write it once, reuse it multiple times; translate it once, reuse the translated chunk multiple times.

Ben’s argument for single-sourcing was and is simple: Write it once, reuse it multiple times; translate it once, reuse the translated chunk multiple times.

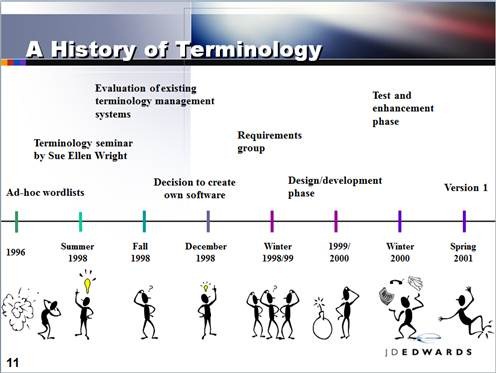

At that time, the J.D. Edwards’ terminology team and project was in its infancy. In fact, the TMS was just about to go live, as the timeline presented in Antwerp shows.

At that time, the J.D. Edwards’ terminology team and project was in its infancy. In fact, the TMS was just about to go live, as the timeline presented in Antwerp shows.

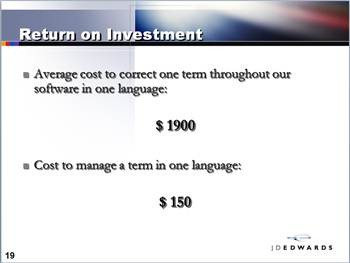

For the ROI (return on investment) study, my colleagues compared the following data:

- What does it cost to change one term throughout the J.D. Edwards software and documentation?

- What does it cost to manage one concept/term?

27 different terms were changed in various languages, and the time it took was measured. Then, the average change time was multiplied by the average hourly translation cost, including overhead. In the J.D. Edwards setting, the average cost to change one term in one language turned out to be $1900.

The average time that it took to create one entry in the terminology database had already been measured. At that early time in the project, it cost $150 per terminological entry.

The average time that it took to create one entry in the terminology database had already been measured. At that early time in the project, it cost $150 per terminological entry.

The cost to manage one entry seems high. Therefore, it is important to note that

- There were three quality assurance steps in the flow of one entry for the source language English, and up to two steps in the flow of one entry for the target languages. So, the resulting entry was highly reliable, and change management was minimal.

- The cost came down dramatically over the months, as terminologists and other terminology stakeholders became more proficient in the process, standards and tool.

Both figures are highly system/environment-dependent. In other words, if it is easy to find and replace a term in the documents, it will cost less. While these figures were first published years ago, they served as the benchmark in the industry and established an ROI model that has since been used and further developed and elaborated on. If you have any opinion, thoughts or can share other information, feel free to add a comment or send me an e-mail.

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying…

Example 2. The VP of content publishing and translation at JDE used the following example to point out that terms and concepts should not be used at will: reporting code, system code, application, product, module, and product code. While everyone in Accounting had some sort of meaning in their head, the concepts behind them were initially not clearly defined. For example, does a product consist of modules? Or does an application consist of systems? Is a reporting code part of a module or a subunit of a product code? And when a customer buys an application is it the same as a product? So, what happens if Accounting isn’t clear what exactly the customer is buying… The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request.

The standards and rules that Demi referred should be reflected in standardized entries in a terminology database and available at the localizers’ fingertips. Now, the tricky part is that, for Japanese, terms representing different concepts than those selected during upfront term selection may need to be standardized. In this case, it is vital that the terminology management system allow requests for entries from downstream contributors, such as the Japanese terminologist or the Japanese localizers. The requests may not make sense to a source terminologist at first glance, so a justification comment speeds up processing of the request. ISO 704, for example, says “a terminology shall include lexical units that are adequately defined in general language dictionaries only when these lexical units are used to designate concepts that form part of the concept system.” Definition by exclusion–that is not a bad start.

ISO 704, for example, says “a terminology shall include lexical units that are adequately defined in general language dictionaries only when these lexical units are used to designate concepts that form part of the concept system.” Definition by exclusion–that is not a bad start.