Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language Bininj Gun-wok say “I cooked the wrong meat for them again,” according to an article from The New Scientist. While these linguistic units do not represent a concept that would come up in a localization environment and Bininj Gun-wok is not one of the languages into which products are localized frequently, if at all, this example shows perfectly well that languages have different ways to represent concepts. And we better not force the system of one language onto another.

Does this look like a cat ran across a keyboard to you? This is how speakers of the indigenous Australian language Bininj Gun-wok say “I cooked the wrong meat for them again,” according to an article from The New Scientist. While these linguistic units do not represent a concept that would come up in a localization environment and Bininj Gun-wok is not one of the languages into which products are localized frequently, if at all, this example shows perfectly well that languages have different ways to represent concepts. And we better not force the system of one language onto another.

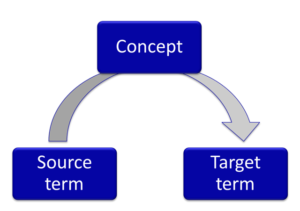

The good thing is we don’t have to. Translators work through the concept. That means, they understand what a term, word or expression (e.g. “I cooked the wrong meat for them again”) means in the source language and then find the target-language equivalent (e.g. abanyawoihwarrgahmarneganjginjeng). Believe me–it takes a lot of analysis by a genius translator to turn a phrase into a perfect one-word equivalent!

The good thing is we don’t have to. Translators work through the concept. That means, they understand what a term, word or expression (e.g. “I cooked the wrong meat for them again”) means in the source language and then find the target-language equivalent (e.g. abanyawoihwarrgahmarneganjginjeng). Believe me–it takes a lot of analysis by a genius translator to turn a phrase into a perfect one-word equivalent!

While there are patterns on how languages represent concepts (e.g. noun-noun, adjective noun), there is no rule that says what is an adjective-noun combination in one language must be an adjective-noun combination in another.

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is.

Localizers often try to create target terms that stick close to the source language pattern, so that they can repeat it when more new terms are created in the source language. That is not a bad idea, as long as they don’t take a shortcut and fail to examine what the concept behind the term is.

A few years ago, the Japanese team working on the localization of a Windows product suggested that ‘compliance report’ be renamed in English. The content publishing team provided background information, but the localizers insisted that it be changed in the English material, because “it was hard to translate into Japanese.” The writers wanted to be good citizens and changed it to ‘status report,’ as the Japanese native speakers had suggested. Not only do ‘compliance’ and ‘status’ not represent the same idea, ‘compliance report’ came up again in another related product. When that product team was asked to change it to ‘status report’, they refused. After all it was correct and clear English.

While it is good practice to provide feedback on neoterms (newly created technical terms) that are culture-laden (e.g. breadcrumb bar) or product names that are to remain in the source language (e.g. Windows Vista), here are the consequences of the above scenario:

If writers, editors, PMs, source terminologists and others working in the source language give in to such pressures from the loc team, they are creating a synonym for a term that worked perfectly well and represented a concept uniquely. Another team that needs to communicate about the same concept will not even thing about looking at a good term, much less changing it. And what if the new term that now works for Japanese doesn’t work for Turkish, French, Danish, Ukrainian…. Instead:

- Avoid synonyms when you can.

- Solicit feedback from other product teams before you change a term.

- Be clear in the source language; customers and translators will understand what you meant.

- Document terms and concepts in a centralized terminology database.

For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead:

For localizers or target terminologists it is important to remember that the product will be released in the target language, whether a source term sounds good or not; in other words “…doesn’t work for my language” doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that source terminology is always perfect. But product teams who get sidetracked on non-issues might not listen the next time there is a real globalization problem. Instead:

- Focus on understanding concepts and finding clear target-language equivalents.

- Spend time giving feedback on real errors or globalization issues.

- And when researching terms, don’t take a shortcut–you would never come up with the perfect abanyawoihwarrgahmarneganjginjeng!